- 2/3 wildlife has vanished since 1970 due to humans (World Wildlife Fund)

- 3 billion fewer birds in North America since 1970 (Science Magazine, 9/19/19)

- 40% of insect species are declining, 30% are endangered. Insects could vanish within a century due to habitat loss (The Guardian, 2/10/19)

No more poisons: Most poisons do little or nothing to solve a problem. Mosquito sprays get 10% of adult mosquitos. Mosquito larvae give us the best opportunity to stop adult biting mosquitos. The larvae grow in water so don’t leave pools or containers of water around your house. But a pail of water with stems or straw fermenting in it can be a trap when you put in the small BT rings (available at most hardware stores). The water with this soil-borne bacteria is safe for dogs and birds to drink but some water animals are sensitive so after use pour it on the ground, not in a stream.

No more bright white outside lights: Half of each day is darkness. Insects exhaust themselves flying at white lights and then can’t breed or pollinate plants. Substitute yellow lights, which do not draw insects. LED bulbs save energy. Yellow LED lights are the best outside lights. Insects pollinate plants, they are essential to the food web. The food web is food makers, food eaters, and decomposers.

Healthy wildlife habitats: Bugs and plants in the same region evolved together. Bugs can make a hole in the stem of a co-evolved plant or eat its leaves because they have evolved the needed mouthparts and can tolerate the chemicals in that plant. The specific bugs get food and housing and the specific plant gets help with pollination or seed dispersal. Certainly plants need self-protection. The world is green because of bitter, tough, and toxic leaves, but tough and toxic leaves are no problem to specific bugs who evolved symbiotically.

The food web of sun to leaves to animals is strong and depends on very old, specific relations. Plants that are far from their regions, that is, non-native plants, are chemically and physically unable to be part of the healthiest food webs.

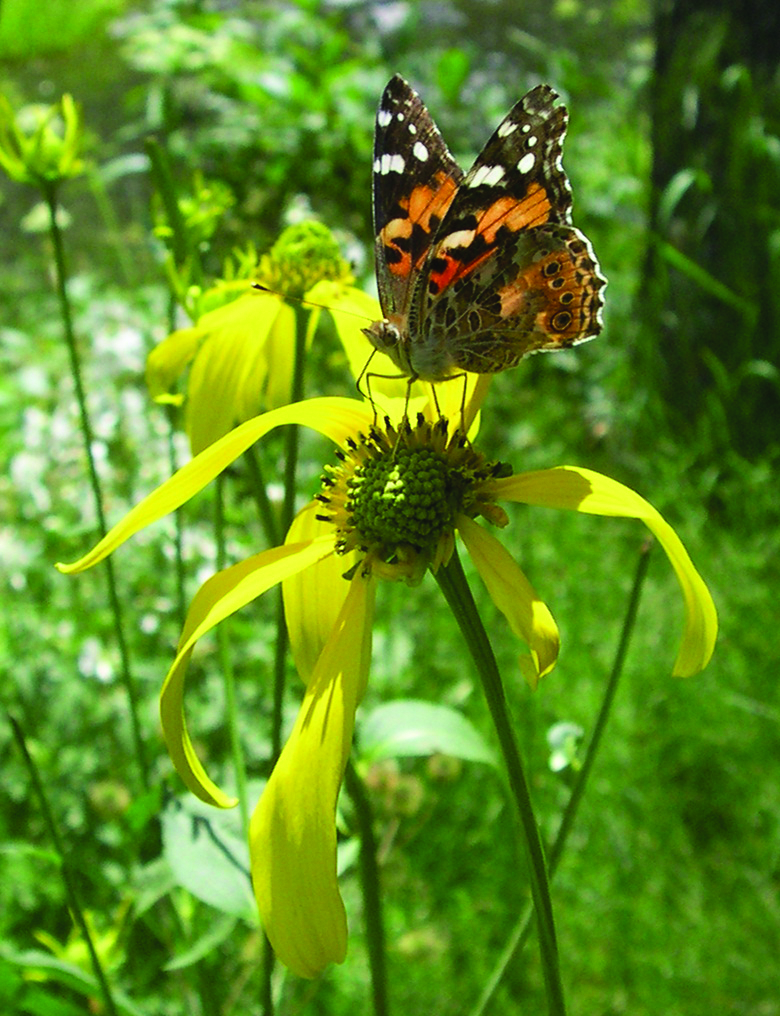

Flying insects—butterflies, bees, moths, beetles, flies—do most of the pollinating of flowering plants. A little note about bees: specialist bees can carry and place pollen in the correct spot to successfully pollinate their plants. Most specialist bees are solitary, don’t sting because they are not protecting hives, and live in the ground. Bees get energy from nectar and protein from pollen. Honeybees, from Europe, are fine as generalists but much less efficient than native bees in pollination.

Birds help too in pollinating flowering plants and in return are fed by those plants. And birds are fed, big time, by bugs. We mostly put out seed for birds. Nature provides seed to land-birds in the fall and winter. In the spring, come baby birds. Baby birds need caterpillars because caterpillars are full of fat and protein in a soft casing, perfect for stuffing down little throats. Only doves and finches can make babies on seed alone, other land-birds need caterpillars. Lots of caterpillars. Baby chickadees, averaging 6-8 in a clutch, need up to 9000 caterpillars while in the nest. After the babies hop out, their parents feed them for another three weeks. Whoa, tired chickadee parents.

The bugs that make these caterpillars are specialists, often using only native plants, and their caterpillar (larvae) are specialists. The right plants are needed. Plant diversity gives protection to soil and animals because everything is always changing. In that diversity are all these special relationships. Native plants offer what’s needed. And among the native plants there are keystone—the most essential—plants that support 90% of the butterflies and moths.

To get started thinking about keystone plants you can go to the National Wildlife Federation: nwf.org, keystone plants by ecoregion. Again, choose from the groupings only those plants that are native to your local region. The eco-regions are given, which include coasts to deserts. For example:

Southern semi-arid Highlands

Trees and shrubs: oaks, pines, cottonwood, willow…

Smaller plants: rabbitbrush/chamisa, sunflowers, goldenrod, yuccas, lupines

To make healthy wildlife habitats, 75% of your garden should be native plants with the emphasis on keystone plants. 25% only can be your nostalgic or eye-candy favorites. Gardens of every size contribute.

Home Grown National Parks: Tiny gardens can bring in great numbers of moths and butterflies and their caterpillars. These gardens add up. Ecologist Doug Tallamy, in his books and videos, has shown me all that is here. He enthusiastically acknowledges his fellow scientists and visionaries, with whom he founded HomeGrownNationalPark.org. Ready as our gardens are to be transformed, so are roadsides, railroad edges, power lines and parks. The monster of barren acreage is The Lawn, defined as a monoculture that is excessively watered, fertilized, herbicided, pesticided and mowed. Lawns in the U.S. make up 40 million acres, almost as much land as all our national parks together—Acadia, Denali, Grand Canyon, Great Smoky Mountains, Haleakala, Yellowstone, plus the 57 others. Remember how to change this. Remove some lawn from around a tree. Roots can prosper and bugs can complete their life cycles—many bugs need to drop from trees and burrow into soil, later to yield more bugs and birds and all kinds of joy.

Habitat: Tallamy’s practical outreach for bringing nature back to sterile land—small and large parcels—is wonderful. It is however essential to remember in planning that the larger the area the better. Human-caused fragmentation destroys biodiversity. That was shown by Tom Lovejoy in his lifelong research in Brazil and elsewhere. He worked steadily with indigenous people to preserve their cultures and the entire Amazon rainforest. He also worked tirelessly for wildlands internationally. Lovejoy died December 25, 2021.

E. O. Wilson died December 26, 2021. Another great conservationist and naturalist, E. O. Wilson passionately believed that we need to set aside half the earth and half the sea as a reserve, making this case in his book, Half-Earth, Our Planet’s Fight for Life. This reserve is not without people, encouraging indigenous people to continue their way of life, but it is fully protected so that most of the earth’s species can continue to live.

Because of human influence on the environment and climate our era has been called Anthropocene, the human era, E.O. Wilson preferred to call it the Eremocene, the Age of Loneliness.